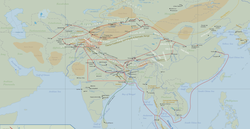

Yesterday I attended a talk by Dr. Pierce Salguero of Penn. State University, part of a series of talks on Chinese medicine organized by Yi-Li Wu and Miranda Brown at the University of Michigan. Professor Salguero started his talk by showing a map of Eurasia, and introduced the term ‘Indo-European Humoral Medicine’, which he uses to describe the common elements between ancient Indian, Greek, and Roman (and to some extent Persian) medical traditions, all of which recognized the four elements of earth, fire, water, and wind, as well as humors such as bile, phlegm, and blood. These ancient cultures were in close communication with each other and shared medical theories. An independent and distinct style of medicine was developing on the other side of Eurasia: Classical Chinese medicine, as exemplified by the 2nd century C.E. text 《黃帝內經》(Yellow Emperor's Internal Classic). This was the medicine of “qi, yin-yang, and the five phases”, a conceptual framework quite distinct from that of ‘humoral medicine’. These two distinct medicines were isolated from each other until the ‘waking up’ of the silk roads (including both land and sea routes), and by the 3rd century C.E. there was widespread communication via these routes. Professor Salguero’s research focuses on the exchange of medical information and practices that were transferred across the silk road networks in the first millennium C.E. He has observed a close relationship between Buddhism and the medical information (goods, items) that was traded throughout this region; with Buddhism acting either as the vehicle for this information, or the inspiration for the transfer of this information. The medical exchanges included medicinal herbs, texts, rituals and deities, and even living individuals who traveled great distances along the silk road and were recorded as having great healing powers in texts of that time. It was during this ‘medieval’ period that the Chinese medicine pharmacopeia exploded – from 365 herbs in the original material medica 《神農本草經》(The Divine Husbander's Herbal Foundation Canon) to thousands of herbs by the Tang dynasty (618-906 C.E.). Much of Professor Salguero’s research has focused on textual exchange during this period – the translation of Sanskrit texts into Chinese. Some of these texts were clearly efforts to integrate foreign knowledge into the pre-existing local understanding of the body, by using qi, yin-yang, and the five phases to make the foreign concepts more understandable to a local audience. There are also examples of popular accounts of Buddhist healers rewritten to match the style of similar stories in Chinese literature. However, other texts clearly try to ‘foreignize’ the material by drawing a distinction between local concepts and the foreign concepts that the author is trying to introduce. Still other texts include both foreignizing and domesticating elements: for example a two-part conversation between a Buddhist and an interlocutor in which a request for information about a particular concept is answered with very foreign sounding explanation, followed by another request for clarification that is responded to in a way that is more familiar. Professor Salguero gave the following example for the translation of the term dhāranī, which is a type of incantation used in Buddhist rituals: The term might be introduced using the Chinese characters 陀羅尼, which is simply a phonetic equivalent (“tuoluoni” in modern pinyin) that sounds similar to the Sanskrit term and doesn’t actually mean anything in Chinese. The first request for an explanation might be met by with the Chinese term 總持, which literally means ‘comprehensively grasp’. This is a type of translation known as a calque, which is a literal translation of the root(s) of the original term. Although this term does mean something in Chinese, it is unlikely that the reader would understand how this term is used; the interlocutor asks for clarification, and lastly the term is explained using the Chinese character 咒, or 神咒. This would be very familiar, as it is a term that had been used for centuries even before Buddhism was introduced to China to refer to magic spells or magic incantations as used by Daoists or others. At this point the interlocutor (and the reader) would have a fairly complete understanding of the original Buddhist concept. There were several other topics covered in this talk, as well as many others brought up during the Q&A period at the end, but in order to keep this post to a reasonable length I will leave those for later posts!

1 Comment

This is a great year to be a Chinese medicine practitioner in Ann Arbor! Besides the Society for Acupuncture Research (SAR) conference to be held April, 2013, there will be no less than four speakers coming to the University of Michigan to give talks about Chinese Medicine! The first is Dr. Pierce Salguero of the Pennsylvania State University, giving a talk this coming Thursday (10/4) entitled “Buddhist Medicine in China: Disease, Healing, and the Body in Cross-cultural Translation”. For a complete list of speakers and dates, please download this PDF.  I have been reading "Doctors East Doctors West" (Norton, 1946) by Dr. Edward H. Hume, an account of his experience setting up the Xiangya (Hsiangya) Hospital and Medical College in Hunan during the tumultuous early decades of the 20th century. In the book there are many accounts of his interactions with the local Chinese medical physicians, whose skills he had many opportunities to observe and greatly respected, and in addition there is a brief account of his introduction to《伤寒论》, in which he compared Zhang Zhongjing's knowledge of typhoid fever to that of his teacher William Osler. I'd like to share his review of what he translated as A Treatise on Typhoid Fever by Chang Chung-ching here, and ask if anybody knows of an earlier English-language review of the text. (Note that the event described below occurred in 1906-07) - - - - - - - - - - Begin Madame T'ao brought her daughter over to the hospital on a special stretcher that had been improvised. "We want to put the girl in your care. All the best Chinese doctors in Changsha have prescribed for her, yet she does not get better." The mother realized how seriously ill the girl was and had decided to ask me to treat her in the hospital. She was ill indeed. Typhoid fever, with a high temperature and delirium--a very gloomy outlook. I gave each of the others in the immediate family a shot of typhoid vaccine, then went ahead with the care of the eighteen-year-old patient, using cooling baths as Osler had taught us. I thought it was a thoroughly modern procedure. Madame T'ao asked me the next day whether I had ever heard of Dr. Chang, one of the most renowned of China's old physicians and at one time mayor of Changsha. "Your use of enemas and of cooling baths reminds me of what my father used to tell me of this celebrated physician's way of treatment. Tomorrow I will bring over, for you to see, one of the volumes of the remarkable essays this old-time physician wrote." The following morning Madame T'ao brought over the first volume of A Treatise on Typhoid Fever, by Chang Chung-ching, published about A.D. 196. It was an astounding discovery to find such a book in Changsha. Here were accurate descriptions of the onset of the fever: chilliness and headache; loss of appetite and nosebleed; temperature rising higher each afternoon. Osler could scarcely have given a clearer picture. More important still, old Dr. Chang had written, "Never use drastic purgatives in this fever. If necessary, use enemas of pig's bile, mixed with a little vinegar, and inserted with a slender bamboo tube. If the fever is high, use cooling baths; they will be found to give strength to the patient and reduce his delirium." Madame T'ao told me more about this historic book, written in Changsha, where our hospital was supposed to be setting the pace in scientific diagnosis and treatment. Her father, who was always reading biographies, especially of the eminent medical men of China, was particularly devoted to this celebrated physician and considered these volumes the first rational treatise on treatment ever written in China. He thought one reason for the fame of the book was its classic style, something all Chinese literati admired, and insisted that this Treatise on Typhoid Fever was in every sense the medical equivalent of The Four Books, which formed the foundation of the Confucian classical literature. In her father's library, she said were several editions, the best being one published during the Sung Dynasty. It was in fourteen volumes and contained two hundred and ninety-seven outlines of treatment and over a hundred prescriptions. Dr. Chang, who received his literary degree during the reign of the Emperor Ling Ti of the Han Dynasty, became interested in typhoid fever when he saw that most of the deaths in his native village over a period of ten years were from this disease. In that time the deaths numbered two-thirds of the two hundred inhabitants. One epidemic so impressed him by its severity that he gave himself over to the study of the causes and symptoms, the treatment and prevention of the disease. A Treatise on Typhoid Fever was the result. Repeated editions of Chang's great work had been issued through the centuries, Madame T'ao told me, and with many commentaries. One of the first of these was by Dr. Wang Shu-ho, China's great authority on the pulse, who lived a century or so after Dr. Chang. From then on, I found that every intelligent Chinese knew about this book. I soon concluded that far more people in China knew about Dr. Chang and his work on typhoid fever than did my countrymen about William Osler and other physicians who had described this fever. During the next few days, as I cared for Madame T'ao's daughter, I felt as if I were listening to the voices of two counselors. Both of them seemed to warn me about symptoms that might appear toward the end of the second week, or a sign that might be peculiarly unfavorable. These two distinguished physicians lived seventeen hundred years apart and in opposite hemispheres; yet each observed something that put him ahead of most of his contemporaries. It was fascinating to discover how many similarities there were between the two. Both emphasized the prime importance of diagnosis; both were bedside clinicians, experienced in interpreting symptoms; both were different from their contemporaries in cautioning against excessive medication and in recommending hydrotherapy. How near together these two great leaders were, though continents and centuries apart! - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - END |

AuthorPractitioner, Translator, Teacher Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed