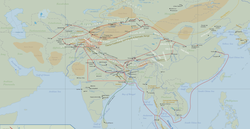

Yesterday I attended a talk by Dr. Pierce Salguero of Penn. State University, part of a series of talks on Chinese medicine organized by Yi-Li Wu and Miranda Brown at the University of Michigan. Professor Salguero started his talk by showing a map of Eurasia, and introduced the term ‘Indo-European Humoral Medicine’, which he uses to describe the common elements between ancient Indian, Greek, and Roman (and to some extent Persian) medical traditions, all of which recognized the four elements of earth, fire, water, and wind, as well as humors such as bile, phlegm, and blood. These ancient cultures were in close communication with each other and shared medical theories. An independent and distinct style of medicine was developing on the other side of Eurasia: Classical Chinese medicine, as exemplified by the 2nd century C.E. text 《黃帝內經》(Yellow Emperor's Internal Classic). This was the medicine of “qi, yin-yang, and the five phases”, a conceptual framework quite distinct from that of ‘humoral medicine’. These two distinct medicines were isolated from each other until the ‘waking up’ of the silk roads (including both land and sea routes), and by the 3rd century C.E. there was widespread communication via these routes. Professor Salguero’s research focuses on the exchange of medical information and practices that were transferred across the silk road networks in the first millennium C.E. He has observed a close relationship between Buddhism and the medical information (goods, items) that was traded throughout this region; with Buddhism acting either as the vehicle for this information, or the inspiration for the transfer of this information. The medical exchanges included medicinal herbs, texts, rituals and deities, and even living individuals who traveled great distances along the silk road and were recorded as having great healing powers in texts of that time. It was during this ‘medieval’ period that the Chinese medicine pharmacopeia exploded – from 365 herbs in the original material medica 《神農本草經》(The Divine Husbander's Herbal Foundation Canon) to thousands of herbs by the Tang dynasty (618-906 C.E.). Much of Professor Salguero’s research has focused on textual exchange during this period – the translation of Sanskrit texts into Chinese. Some of these texts were clearly efforts to integrate foreign knowledge into the pre-existing local understanding of the body, by using qi, yin-yang, and the five phases to make the foreign concepts more understandable to a local audience. There are also examples of popular accounts of Buddhist healers rewritten to match the style of similar stories in Chinese literature. However, other texts clearly try to ‘foreignize’ the material by drawing a distinction between local concepts and the foreign concepts that the author is trying to introduce. Still other texts include both foreignizing and domesticating elements: for example a two-part conversation between a Buddhist and an interlocutor in which a request for information about a particular concept is answered with very foreign sounding explanation, followed by another request for clarification that is responded to in a way that is more familiar. Professor Salguero gave the following example for the translation of the term dhāranī, which is a type of incantation used in Buddhist rituals: The term might be introduced using the Chinese characters 陀羅尼, which is simply a phonetic equivalent (“tuoluoni” in modern pinyin) that sounds similar to the Sanskrit term and doesn’t actually mean anything in Chinese. The first request for an explanation might be met by with the Chinese term 總持, which literally means ‘comprehensively grasp’. This is a type of translation known as a calque, which is a literal translation of the root(s) of the original term. Although this term does mean something in Chinese, it is unlikely that the reader would understand how this term is used; the interlocutor asks for clarification, and lastly the term is explained using the Chinese character 咒, or 神咒. This would be very familiar, as it is a term that had been used for centuries even before Buddhism was introduced to China to refer to magic spells or magic incantations as used by Daoists or others. At this point the interlocutor (and the reader) would have a fairly complete understanding of the original Buddhist concept. There were several other topics covered in this talk, as well as many others brought up during the Q&A period at the end, but in order to keep this post to a reasonable length I will leave those for later posts!

1 Comment

Jian Guo

1/15/2020 11:21:50 am

Any more information that connects Buddhism and TCM than just some historical terms? I haven't seen any get high level Buddhist teachers to discuss in depth about healing the body, they usually talks about the mind and philosophy, TCM and TCM doctors are more open to both subjects, if both work together, there will be a lot of progress.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPractitioner, Translator, Teacher Archives

March 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed